A comment on a previous post reminded me of why I am not going to be a surgeon. I loved surgery, at least, the surgery part of it, and I could see myself enjoying the job. But two things keep me from it: surgeons, and needles.

Now I'm not really afraid of needles in the generalized, five-year-old-getting-a-shot sense. Getting my own blood drawn, I'll offer to help the phlebotomist. I like to watch, and one day I'll probably try putting in my own IV, just for the heck of it.

Ok, maybe not, that's kinda gross.

But the point is, in the abstract, needles don't bother me in the slightest. What bothers me is getting stuck with needles that have already stuck someone whose Hep C/HIV status you don't know, or worse, you do know, and don't like.

This has happened to me, on three separate occasions. The first was my own fault, I pricked myself while suturing, a fairly common occurence, and one I've seen experienced surgeons replicate. Once I saw a surgeon, the eminent aforementioned Dr. Harb, stick himself not once, nor even twice, but four times, in the same operation. Just a bad day I guess. But I digress.

The second time was scary, and an opportunity I missed to practice Christian charity. A tech stabbed me with a huge, bloody, CT-1 needle loaded with 2-0 Vicryl suture as he was trying to take it off the field. Very much his fault, and even the surgeon told him to watch what he was doing. I didn't take the opportunity to do anything but glower at the tech over my mask, proving that my temperment is malleable in all the wrong ways in a given environment. I still regret that.

Third, the real charm, was during a c-section, though not a crash one. The attending was pimping the chief resident during this operation, and his increasingly impolitic observations on her performance riled her up. She started making huge, dramatic movments with both scissors and needle, and in one of her exasperated flourishes, she stabbed me.

After these incidents, I had to go down to Occupational Health, fill out a bunch of forms, and then go get my blood drawn, as another team drew blood on the patient. I guess none of my patients were considered "high risk" so I never took the antiretroviral drugs and interferon which are sometimes given to hapless individuals in this situation. In hindsight, it makes me angry I wasn't given the drugs, since the status of two of the patients was unknown. Fortunately though, all the tests came back negative, and I didn't develop a disease which would kill me.

Waiting for the results of tests ensuring neither I nor the patients had HIV or Hepatitis C was horrible. An experience I don't want to repeat.

So I pooled my thoughts. I realized that the stress of the job, and the people I worked for, had changed my personality into someone I didn't like. I knew coming into medicine the risk of getting seriously ill or dying from patient contact was not zero, but I also realized that 2 out of 3 times something potentially life-threatening happened to me, it was the fault of another person, in the OR. I decided right there that surgery was not the best path for me.

Saturday, April 29, 2006

Friday, April 28, 2006

Dietary counselling

Today I saw John Belushi in clinic.

Not really of course, since John is dead, and this guy was ten years old, but the point is, the obesity epidemic is real. The problem is that he came in because his mom was concerned about a rash, and so my preceptor didn't want to touch on the issue of the kid's weight.

So I acceded to her direction, and dealt only with the guy's rash, but it broke my heart to see a ten year old sitting on the exam table playing with his minature beer belly while his mom and I discussed his treatment. I should have spoken up about his diet anyway, but my preceptor's point was "that's a job for his primary care provider." Next time, I'm going to talk about diet anyway.

I'll probably be seeing little JB in my cardiology practice in 30 years, when his lifestyle and habitus catch up with him. But I'd rather not, for his sake.

Not really of course, since John is dead, and this guy was ten years old, but the point is, the obesity epidemic is real. The problem is that he came in because his mom was concerned about a rash, and so my preceptor didn't want to touch on the issue of the kid's weight.

So I acceded to her direction, and dealt only with the guy's rash, but it broke my heart to see a ten year old sitting on the exam table playing with his minature beer belly while his mom and I discussed his treatment. I should have spoken up about his diet anyway, but my preceptor's point was "that's a job for his primary care provider." Next time, I'm going to talk about diet anyway.

I'll probably be seeing little JB in my cardiology practice in 30 years, when his lifestyle and habitus catch up with him. But I'd rather not, for his sake.

Thursday, April 27, 2006

Speechless, indeed

A sad story

My thoughts:

One of the things which has become more clear to me while in medical school (there aren't many) is that people are not basically good. There is good in the world, and it is worth fighting for, but it will always be a struggle by kind hearted individuals against an indifferent crowd.

My thoughts:

One of the things which has become more clear to me while in medical school (there aren't many) is that people are not basically good. There is good in the world, and it is worth fighting for, but it will always be a struggle by kind hearted individuals against an indifferent crowd.

Lectures and Ramblings

A day of lectures. Nothing terribly memorable, except that I found out, about ten minutes before class was to begin, that I had to have a "1-2 page paper relating to the issues of professionalism or ethics" typed up and ready to discuss with the class. I was a bit concerned, but then this, my blog occurred to me. So I went online, printed up a previous post, and took that. Saved!

The discussion itself touched on professionalism, but soon became a discussion of the shortcomings in modern medical education. We talked a bit about what is called the "unwritten curriculum" of medical school, which refers to the fact that though we are constantly taught sympathy, compassion, and concern, as soon as we reach the wards, we see sarcasm, cynicism, and laziness. It makes effecting any change difficult, for actions truly speak louder than words. It is apparently the subject of some debate in the educational medical community.

Certainly, I've seen the attitude, and I've seen the effects, even in myself. I was not a person I would associate with when I finished my surgery rotation, and a huge part of that change in my personality was due to my surroundings. I am no longer surprised at statistics like "physicians are more than twice as likely than the general population to kill themselves" and "physicians divorce at a rate 10 to 20 percent higher than the rest of the population" and "even physicians who stay married report more unhappy marriages than the general population." Some of these statistics are the subject of considerable debate, and some are old, but even the least controversial studies point to the profession as a risk factor for divorce and suicide. Scary. And I read another study recently which polled interns across the country and found a 75% rate of suicidal ideation.

Thoughts like this are the ones that didn't come to me until after I'd gotten to medical school. I don't remember what I thought it would be like, but I know I didn't expect most of this life. Certainly the vast majority of my classmates would say their perceptions of medicine before coming were wildly diferent from reality. A sizable majority would say they've considered suicide since coming to medical school, and in my class, with about 40 married students, there have already been three divorces in the past two years. No one has committed suicide, thankfully, but statistically, it wouldn't be unusual.

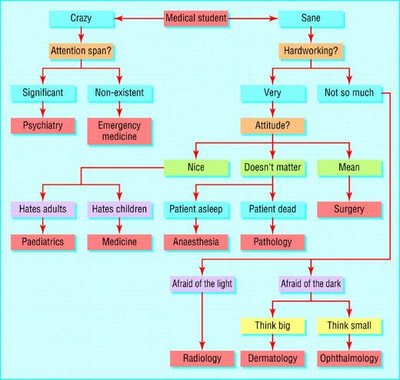

I wonder, often, what peculiar undiagnosed mental disease we all share to stay.

The discussion itself touched on professionalism, but soon became a discussion of the shortcomings in modern medical education. We talked a bit about what is called the "unwritten curriculum" of medical school, which refers to the fact that though we are constantly taught sympathy, compassion, and concern, as soon as we reach the wards, we see sarcasm, cynicism, and laziness. It makes effecting any change difficult, for actions truly speak louder than words. It is apparently the subject of some debate in the educational medical community.

Certainly, I've seen the attitude, and I've seen the effects, even in myself. I was not a person I would associate with when I finished my surgery rotation, and a huge part of that change in my personality was due to my surroundings. I am no longer surprised at statistics like "physicians are more than twice as likely than the general population to kill themselves" and "physicians divorce at a rate 10 to 20 percent higher than the rest of the population" and "even physicians who stay married report more unhappy marriages than the general population." Some of these statistics are the subject of considerable debate, and some are old, but even the least controversial studies point to the profession as a risk factor for divorce and suicide. Scary. And I read another study recently which polled interns across the country and found a 75% rate of suicidal ideation.

Thoughts like this are the ones that didn't come to me until after I'd gotten to medical school. I don't remember what I thought it would be like, but I know I didn't expect most of this life. Certainly the vast majority of my classmates would say their perceptions of medicine before coming were wildly diferent from reality. A sizable majority would say they've considered suicide since coming to medical school, and in my class, with about 40 married students, there have already been three divorces in the past two years. No one has committed suicide, thankfully, but statistically, it wouldn't be unusual.

I wonder, often, what peculiar undiagnosed mental disease we all share to stay.

Monday, April 24, 2006

Parenthood

Aside from all the organic, scary situations childbirth puts people, I've been thinking a lot about parenthood in general. What started it was first, the inpatient peds ward, but what really got me thinking seriously, in more than a knee-jerk now-I'm-never-going-to-have-kids way, was a book I found in the nurses' station at about 3am while I was waiting for some lab tests to come back. The book was about "how to deal with death in children" and overall, seemed well thought out. But as I flipped idly through it, I came across a poem by Kahlil Gibran, entitled "Children." I recommend reading it all, it isn't long. But this struck me first:

[Your children] come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you, yet they belong not to you.

It was that line which pointed out the essential silliness of my conclusions. Children, any children, even mine, should I ever have any, belong only to themselves and to G-d. Gibran follows that thought with:

You may strive to be like them, but seek not to make them like you.

For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday.

You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth.

This is the essence of parenthood I think. Parents can impart a great deal to their children, but ultimately, their course is only roughly determined by those archers. More to my point in experience, I am in medicine because it is the best way I can bring something good to the world. But a more powerful way to do the same is to leave children behind to carry on that spirit, that idea. And that is a cause worth risking for, even risking having children who wind up in inpatient peds. Even though a parent cannot control precisely where they go, cannot predict the winds that will buffet those arrows. I think Gibran had a more famous book in mind when he wrote those words, a book which says:

Like arrows in the hand of a warrior,

So are the children of one's youth.

Happy is the man who has his quiver full of them

Indeed. Though that was written at a time that most the kids I have seen treated would have died, I think the message is still timeless. It must be.

I hope, or I could not live.

My thoughts on all this have been perpetuated by another album I've been listening to lately, Birds of My Neighborhood, by the Innocence Mission (again). It's quite possibly the best album I've ever heard. Most of the songs are quite personal explorations of the singer's sorrow upon learning she could not have children.* The poetry is heart-wrenching, but masterfully avoids being maudlin or cheap. I don't want to turn this into an album review though. The point is that the sadness of not having children seems it must be at least as powerful as that of having children "born to pain" as I phrased it earlier.

Even more, the point is that children are not the end of existence. Karen Peris (the singer) comes to this conclusion, though she doesn't want to, in her penultimate song on the album, with this powerful stanza:

July, July,

The man I love and I

Will lift our heads together

July, July,

I've seen the greatest light.

Too much light to deny.

Despite her pain, her faith is what truly matters. It is so with us all.

*Edit: Though this was certainly the case when she wrote the song, the Peris' have since had children. Like Hannah with Samuel, perhaps.

[Your children] come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you, yet they belong not to you.

It was that line which pointed out the essential silliness of my conclusions. Children, any children, even mine, should I ever have any, belong only to themselves and to G-d. Gibran follows that thought with:

You may strive to be like them, but seek not to make them like you.

For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday.

You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth.

This is the essence of parenthood I think. Parents can impart a great deal to their children, but ultimately, their course is only roughly determined by those archers. More to my point in experience, I am in medicine because it is the best way I can bring something good to the world. But a more powerful way to do the same is to leave children behind to carry on that spirit, that idea. And that is a cause worth risking for, even risking having children who wind up in inpatient peds. Even though a parent cannot control precisely where they go, cannot predict the winds that will buffet those arrows. I think Gibran had a more famous book in mind when he wrote those words, a book which says:

Like arrows in the hand of a warrior,

So are the children of one's youth.

Happy is the man who has his quiver full of them

Indeed. Though that was written at a time that most the kids I have seen treated would have died, I think the message is still timeless. It must be.

I hope, or I could not live.

My thoughts on all this have been perpetuated by another album I've been listening to lately, Birds of My Neighborhood, by the Innocence Mission (again). It's quite possibly the best album I've ever heard. Most of the songs are quite personal explorations of the singer's sorrow upon learning she could not have children.* The poetry is heart-wrenching, but masterfully avoids being maudlin or cheap. I don't want to turn this into an album review though. The point is that the sadness of not having children seems it must be at least as powerful as that of having children "born to pain" as I phrased it earlier.

Even more, the point is that children are not the end of existence. Karen Peris (the singer) comes to this conclusion, though she doesn't want to, in her penultimate song on the album, with this powerful stanza:

July, July,

The man I love and I

Will lift our heads together

July, July,

I've seen the greatest light.

Too much light to deny.

Despite her pain, her faith is what truly matters. It is so with us all.

*Edit: Though this was certainly the case when she wrote the song, the Peris' have since had children. Like Hannah with Samuel, perhaps.

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Crash section

Seeing more than one worried face hurrying into a patient's room is never a good sign. But for a medical student, it usually signals a learning opportunity. So today, when I noticed a much greater than usual bustle around a laboring woman's room, I slipped in with one of the techs and made myself useful.

The patient's unborn child was experiencing "late decels." This is when the baby's heart rate drops after the mother's uterus starts contracting. This means the blood supply to the placenta is being cut off, which obviously isn't good for the kid. It also means the mother has to deliver the baby as quickly as possible. So I assisted setting up the warmer, where the newborn would be placed, as the obstetricians tried their best to get the kid out.

No luck with normal technique, so they started using forceps. Not a pleasant image, and is is almost shocking to realize that essentially the same design has been in use since the 1700s. This usually works pretty well, but even here, the OB docs weren't having any luck. The nurses were getting a little worried, because the real pediatrician hadn't shown up yet, and they are definitely necessary in this situation.

No luck with normal technique, so they started using forceps. Not a pleasant image, and is is almost shocking to realize that essentially the same design has been in use since the 1700s. This usually works pretty well, but even here, the OB docs weren't having any luck. The nurses were getting a little worried, because the real pediatrician hadn't shown up yet, and they are definitely necessary in this situation.

This is when the OB staff doc made a frighteningly calm pronouncement. He simply said "all right, let's go to crash c-section" and the entire room emptied, except me (who didn't know what to do), the nurse midwife, and the doc himself. Every other soul sprinted down the hallway, joining the pediatrician who had just walked in, to prep an operating room. I followed them, and donned a mask and gloves with the rest of the crowd. It was then my job to stick my head out of the OR and call out when, far down the hallway, I could see the patient being wheeled out of her room.

From the time we left the patient's room, until the whole OR was prepped and ready to go, was about five minutes. I saw the patient being wheeled out of her room on her bed, and from that point until the time she was on the table, with anesthesia putting her under, was another minute. I've never seen an OR move that fast. Surgeons, for all their skills, are normally cautious and deliberate, which only makes sense when someone's life is in question.

Now once the patient is unconscious and the OB/Gyn doc is ready to cut, it is "standard of care," meaning the absolute minumum required, for the baby to be in the pediatrician's hands one minute later. If anything, this was better than that. Three cuts with the scalpel, and the surgeon was pulling the baby's head out of the abdomen. Seconds later, a massive resuscitation of a very blue, very motionless baby was underway.

I was pretty worried at this point. I've seen and been part of close to 100 deliveries now, and this was the worst looking kid I've seen yet. But modern medicine is surpassingly capable. According to the delivery note, it took 3 minutes to get the baby girl breathing. I would have guessed half an hour. But she hasn't looked back since, and when I left this evening, was indistinguishable from any other healthy infant on the ward. She didn't even spend time in the NICU.

Amazing.

The patient's unborn child was experiencing "late decels." This is when the baby's heart rate drops after the mother's uterus starts contracting. This means the blood supply to the placenta is being cut off, which obviously isn't good for the kid. It also means the mother has to deliver the baby as quickly as possible. So I assisted setting up the warmer, where the newborn would be placed, as the obstetricians tried their best to get the kid out.

No luck with normal technique, so they started using forceps. Not a pleasant image, and is is almost shocking to realize that essentially the same design has been in use since the 1700s. This usually works pretty well, but even here, the OB docs weren't having any luck. The nurses were getting a little worried, because the real pediatrician hadn't shown up yet, and they are definitely necessary in this situation.

No luck with normal technique, so they started using forceps. Not a pleasant image, and is is almost shocking to realize that essentially the same design has been in use since the 1700s. This usually works pretty well, but even here, the OB docs weren't having any luck. The nurses were getting a little worried, because the real pediatrician hadn't shown up yet, and they are definitely necessary in this situation.This is when the OB staff doc made a frighteningly calm pronouncement. He simply said "all right, let's go to crash c-section" and the entire room emptied, except me (who didn't know what to do), the nurse midwife, and the doc himself. Every other soul sprinted down the hallway, joining the pediatrician who had just walked in, to prep an operating room. I followed them, and donned a mask and gloves with the rest of the crowd. It was then my job to stick my head out of the OR and call out when, far down the hallway, I could see the patient being wheeled out of her room.

From the time we left the patient's room, until the whole OR was prepped and ready to go, was about five minutes. I saw the patient being wheeled out of her room on her bed, and from that point until the time she was on the table, with anesthesia putting her under, was another minute. I've never seen an OR move that fast. Surgeons, for all their skills, are normally cautious and deliberate, which only makes sense when someone's life is in question.

Now once the patient is unconscious and the OB/Gyn doc is ready to cut, it is "standard of care," meaning the absolute minumum required, for the baby to be in the pediatrician's hands one minute later. If anything, this was better than that. Three cuts with the scalpel, and the surgeon was pulling the baby's head out of the abdomen. Seconds later, a massive resuscitation of a very blue, very motionless baby was underway.

I was pretty worried at this point. I've seen and been part of close to 100 deliveries now, and this was the worst looking kid I've seen yet. But modern medicine is surpassingly capable. According to the delivery note, it took 3 minutes to get the baby girl breathing. I would have guessed half an hour. But she hasn't looked back since, and when I left this evening, was indistinguishable from any other healthy infant on the ward. She didn't even spend time in the NICU.

Amazing.

Saturday, April 15, 2006

Children and Peds Clinic

Peds clinic was pretty much what I expected. Runny noses and coughs, with well baby checks thrown in occasionally. A welcome change from Patau syndrome, carnitine deficient cardiomyopathy, and HIE.

The really sick kids have been tough for me to deal with. Seeing them, with so little hope of recovery, makes me think I would have a very tough time having children of my own. I admire the courage of those who have children, who have the faith to trust G-d to give what He will in their lives. But I would worry that my children would be like those I've treated, only born to suffer. I still don't know that my faith is strong enough to have children, to run that risk.

Most of what I feel here is my natural pessimism coupled with anecdotal experience of the worst nature can throw at humanity. But even recognizing that, I still feel it.

Probably, I'll just try not to think too hard about it when the time comes. Almost certainly, there's a bit of cowardice in that reasoning. Thankfully, right now I don't have to worry about having children, since I haven't found the girl yet. But every time I think of having children of my own, the images of my patients, of my embryology texts, come to mind.

Which is why the peds clinic has been good. Here I've seen dozens of kids, usually about 14 a day (in 6 hours, you do the math) forming a steady stream of normal, happy kids with runny noses or ear aches. It helps balance a perception skewed by experience in a hospital renowed for its ability to deal with "zebras," those medical entities so rare they are never seen elsewhere. It's been, at the very least, a restoration of perspective.

I've been thinking a lot about parenthood in general lately, but the rest of that's going to wait for a further post.

The really sick kids have been tough for me to deal with. Seeing them, with so little hope of recovery, makes me think I would have a very tough time having children of my own. I admire the courage of those who have children, who have the faith to trust G-d to give what He will in their lives. But I would worry that my children would be like those I've treated, only born to suffer. I still don't know that my faith is strong enough to have children, to run that risk.

Most of what I feel here is my natural pessimism coupled with anecdotal experience of the worst nature can throw at humanity. But even recognizing that, I still feel it.

Probably, I'll just try not to think too hard about it when the time comes. Almost certainly, there's a bit of cowardice in that reasoning. Thankfully, right now I don't have to worry about having children, since I haven't found the girl yet. But every time I think of having children of my own, the images of my patients, of my embryology texts, come to mind.

Which is why the peds clinic has been good. Here I've seen dozens of kids, usually about 14 a day (in 6 hours, you do the math) forming a steady stream of normal, happy kids with runny noses or ear aches. It helps balance a perception skewed by experience in a hospital renowed for its ability to deal with "zebras," those medical entities so rare they are never seen elsewhere. It's been, at the very least, a restoration of perspective.

I've been thinking a lot about parenthood in general lately, but the rest of that's going to wait for a further post.

Thursday, April 13, 2006

Music reviews

One of the most beautiful albums I've ever heard.

One of the most beautiful albums I've ever heard.I'm not a music reviewer. I don't really have the time or poetic voice to say what it is I like about an album or artist in a way that makes any sense, and I think I'm no longer going to try to write reviews of what I'm listening to. So I'm just going to say I love this album.

5/5 stars

Just a lecture

We had a lecture today on Forensic Pediatrics. These are the experts in child abuse, in determining how children are abused and die at the hands of their parents and caretakers. I could never do that job. The pictures alone were bad enough.

Tuesday, April 11, 2006

Blenders etc.

My dad had a job which often involved getting up at the crack of gloom, and over the years, he developed a breakfast routine which involved putting a few bananas, some ice cream, yogurt, wheat germ, protein powder, raw eggs, and milk into a blender and making a sort of breakfast smoothie. I thought it was revolting at the time, and I couldn't see how anyone choked down a blender full of the stuff.

My dad had a job which often involved getting up at the crack of gloom, and over the years, he developed a breakfast routine which involved putting a few bananas, some ice cream, yogurt, wheat germ, protein powder, raw eggs, and milk into a blender and making a sort of breakfast smoothie. I thought it was revolting at the time, and I couldn't see how anyone choked down a blender full of the stuff.Enter medical school.

Now I have the job involving getting up at various ungodly hours of morning (please, it's a phrase, no theological commentary) and I've found I'm skipping breakfast a lot. Buckwheat kasha takes some time to make, and it's not all that nourishing. Boiled or poached eggs, my other favorite? Forget it. When I get up, it's all I can do to stagger into the shower, and then pour from my automatic-timer-start-coffee-maker before I head out the door, usually about five minutes later than I feel I ought to be. Open flames and hot water? That's begging for trouble.

So, in the interests of getting a breakfast which has some calories and protein, I've bought a blender. It's a thing of beauty actually, shining there on my counter. And I've already tried it out. The texture is somewhat different, probably because, due to my medical training, I can't bring myself to add raw eggs to the mix. But it's not bad. Not bad at all...

I've noticed my culinary bent has been blunted by medical school. I don't do nearly as much cooking my own stuff anymore, and what I do is fast or minimally demanding: stir fry, with frozen vegetables (gasp!). Anything in my crock pot (possibly the greatest invention ever). I dream of breadmakers. Sometimes I fall even farther, and there's a Red Baron pizza and some waffles in my freezer right now. I can feel my arteries hardening just thinking about it.

Which is probably why I've discovered a taste for sardines. Fish are good for you, and on a whim about a year ago, I tried sardines for the first time. I can't believe what I've been missing. Granted, my friends won't sit next to me at lunch, and it's probably a good thing I don't eat in any of the exam rooms, but wow, it doesn't get much better than some boneless, skinless sardines with some soy sauce and crackers. Maybe I need to get out more. But I can't, my blender is calling...

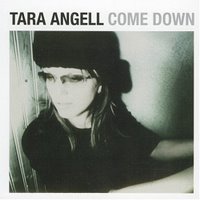

Tara Angell - Come Down

At the Matisyahu concert on Sunday, the local college radio station was giving away free CDs. Just a big box full of them, with no organization. Some didn't even have cases. But I did what any music lover would: grabbed a stack at random and said thanks. I've been going through them, and a few are ok, several are complete wastes of the plastic they're printed on. But this one is amazing.

At the Matisyahu concert on Sunday, the local college radio station was giving away free CDs. Just a big box full of them, with no organization. Some didn't even have cases. But I did what any music lover would: grabbed a stack at random and said thanks. I've been going through them, and a few are ok, several are complete wastes of the plastic they're printed on. But this one is amazing.I listened to this one the first time on my drive to work yesterday. And I was tempted to camp out in the car, and be late for my first patient, so that I could listen to the rest of this album. Tara's voice is rough, but real. Think Emmylou Harris or Lucinda Williams. In fact, my first thought was that this sounded a lot like Emmylou, but that's unfair, since that master performer has gone through almost as many style changes as Madonna, though with more grace. My next thought was Lucinda Williams. I didn't know anything about Tara at that point, but it turns out she has actually played with Lucinda, who apparently loves her music.

More to the point of the album though, this one has powerful lyrics, moving melodies, and perfect suited intrumental production. Spare, to balance the richness of Tara's voice. Just guitar, drums, some keyboards. Very melodic, not in the Keane, "I am going to be humming this for weeks" sense. More like the Decemberists, with less scandalous lyrics. Sombre, mood-setting, but not ambient.

The second thing you notice about this album is that it's an album in the clasic sense. The songs progress through naturally, and it makes sense to listen to them in order. From the rocking opening tracks to the last mournful note of the close, this is a single piece of art.

Excellent, excellent album.

5/5 stars

Monday, April 10, 2006

The otoscope

Sometimes I laugh at my patients. I can't help myself. And today was no different.

I'm in clinic, seeing a lot of well baby exams, mostly happy, healthy kids, with the occasional runny nose, or cough, just like I expected. And the third or fourth patient of the day is a beautiful little girl, about 15 months old, who looked like she didn't know whether to smile or cry when I walked in. She ended up doing both for a short time, while I talked to mom.

I'm going through the well baby check list, asking mom if her daughter is saying single words, how many, etc. And apparently her daughter, Hope, I'll call her, is saying "mama" and "dada" and "yes" and "no." Fairly typical. Children don't start putting two words together in a phrase until about two years old. I told mom that, and everything's good.

I start on the physical exam. This was already getting difficult, because Hope did not like my stethoscope. I let her play with it a bit, and she got a lot less worried, and stopped crying, but as soon as I put it on, I was glad that the earpieces are sound-proof, because the little girl screamed and started crying again. I felt really bad, but with mom's help, we calmed her down, I listened to heart and lungs, and we're on a roll.

See we're told to start with heart and lungs on little kids, because the stethoscope is pretty non-threatening. But nobody ever likes the otoscope. Hope was no exception. Usually though, kids just cry or jerk away. This one was a little more dramatic. Hope took one look at the otoscope and shrieked "OH MY GOD" at the top of her small lungs, in that range only infants and dog whistles can reach, and threw her arms toward mom for rescue.

See we're told to start with heart and lungs on little kids, because the stethoscope is pretty non-threatening. But nobody ever likes the otoscope. Hope was no exception. Usually though, kids just cry or jerk away. This one was a little more dramatic. Hope took one look at the otoscope and shrieked "OH MY GOD" at the top of her small lungs, in that range only infants and dog whistles can reach, and threw her arms toward mom for rescue.

I couldn't help it, I started laughing. This little girl, who is only saying "mama" and "dada" according to mom, had figured at least one phrase out. And hearing that from an infant, coupled with the truest look of stark terror I've ever seen, was just too much. Mom started laughing too, which was good. When I was relating the story to my preceptor, her first comment was "well I guess she's using two word phrases now."

I'm in clinic, seeing a lot of well baby exams, mostly happy, healthy kids, with the occasional runny nose, or cough, just like I expected. And the third or fourth patient of the day is a beautiful little girl, about 15 months old, who looked like she didn't know whether to smile or cry when I walked in. She ended up doing both for a short time, while I talked to mom.

I'm going through the well baby check list, asking mom if her daughter is saying single words, how many, etc. And apparently her daughter, Hope, I'll call her, is saying "mama" and "dada" and "yes" and "no." Fairly typical. Children don't start putting two words together in a phrase until about two years old. I told mom that, and everything's good.

I start on the physical exam. This was already getting difficult, because Hope did not like my stethoscope. I let her play with it a bit, and she got a lot less worried, and stopped crying, but as soon as I put it on, I was glad that the earpieces are sound-proof, because the little girl screamed and started crying again. I felt really bad, but with mom's help, we calmed her down, I listened to heart and lungs, and we're on a roll.

See we're told to start with heart and lungs on little kids, because the stethoscope is pretty non-threatening. But nobody ever likes the otoscope. Hope was no exception. Usually though, kids just cry or jerk away. This one was a little more dramatic. Hope took one look at the otoscope and shrieked "OH MY GOD" at the top of her small lungs, in that range only infants and dog whistles can reach, and threw her arms toward mom for rescue.

See we're told to start with heart and lungs on little kids, because the stethoscope is pretty non-threatening. But nobody ever likes the otoscope. Hope was no exception. Usually though, kids just cry or jerk away. This one was a little more dramatic. Hope took one look at the otoscope and shrieked "OH MY GOD" at the top of her small lungs, in that range only infants and dog whistles can reach, and threw her arms toward mom for rescue.I couldn't help it, I started laughing. This little girl, who is only saying "mama" and "dada" according to mom, had figured at least one phrase out. And hearing that from an infant, coupled with the truest look of stark terror I've ever seen, was just too much. Mom started laughing too, which was good. When I was relating the story to my preceptor, her first comment was "well I guess she's using two word phrases now."

Sunday, April 09, 2006

Next Step

I am done with the inpatient peds ward. And, with the exception of four fitful hours of sleep spent on a couch with not one, but two hard wooden bars disturbing the linear cushion upon which I lay, I have been awake since 5 am yesterday morning. Of course, it's my own fault for scheduling a call night prior to a concert, but hey, you have to stay sane, right? In other news, Matisyahu is excellent in concert. The man's beatboxing skills are second to none, and actually outdid the turntablist who opened for him.

Thursday, April 06, 2006

Quality or Quantity?

I've had occasion to consider this with one of my patients. She is only a few months old, but she suffered some considerable complications during or before her birth, it isn't clear which. She will likely never progress from her current state, which is that she can swallow, weakly and only occasionally, she cannot protect her airway, so she aspirates food into her lungs, and she suffers recurrent seizures. She has an EEG displaying burst supression, which is just one step removed from brain dead. In a particularly difficult patient encounter, our pediatric neurologist told the father that, though pediatric brain injury prognosis is difficult to predict, his daughter would likely never feed herself, walk, comunicate, see, hear, or even have a thought. The father's response was "why didn't you kill her along time ago then?"

I've had occasion to consider this with one of my patients. She is only a few months old, but she suffered some considerable complications during or before her birth, it isn't clear which. She will likely never progress from her current state, which is that she can swallow, weakly and only occasionally, she cannot protect her airway, so she aspirates food into her lungs, and she suffers recurrent seizures. She has an EEG displaying burst supression, which is just one step removed from brain dead. In a particularly difficult patient encounter, our pediatric neurologist told the father that, though pediatric brain injury prognosis is difficult to predict, his daughter would likely never feed herself, walk, comunicate, see, hear, or even have a thought. The father's response was "why didn't you kill her along time ago then?"Though of course actively euthanizing patients in prima facie wrong, I don't know that answer is a good one. Should patients with no hope of recovery be kept alive like this? It's not like that media circus Terri Schiavo case, here the patient has never interacted with anyone. She was born unresponsive and displays nothing but the most primitive of reflexes now. She is only alive because of medical miracles and heroic support measures undertaken at birth, but right now, she doesn't need anything but a tube feed. The argument against letting Mrs. Schiavo die was that a tube feed is not a heroic measure. But I think that's a poor one in this situation.

True, it isn't heroic, but what is heroism but defense of a worthy cause? I'm no longer able to say I believe life is, in the abstract, a worthy cause. I don't know what is. What is it that makes a life worth defending? How do we define "humanness" here? "In the image of God we are made" but how much of that image is interaction, is thought, is contribution, is soul? And how much is the "crude matter" which comprises our physical form?

On the Bright Side

I'm no happier with the way this rotation is going. But there are two shining lights here. One, there are only two more days left with this part of it, and two, this part of it is not a disproportionate part of my grade. I would add that three is the fact that I get to review all the people involved, but a) I don't think that matters to my grade much and b) I'm too nice to really say anything like the cathartic pen-lashing I'd desire.

Wednesday, April 05, 2006

One of Those Days

Some days, nothing goes right and your computer account that allows you to look up patient information (and which has been "in the works" according to the tech support people) is still broken after a week of pestering. Some days your chief resident calls you aside and kindly but frankly says she has concerns that you're even functioning as a low-level third year student, much less one about to enter fourth year. Some days your senior resident makes a point of reprimanding you in front of your intern, your chief and your attending.

Some days, I hate my job. This is one of those days.

Some days, I hate my job. This is one of those days.

Monday, April 03, 2006

One of those people

I was not on top of my game this morning. No excuses, I was just off. Way off.

So, on rounds this morning, I'm trying to relate the stories of each patient to the team. This is kinda funny, since everyone already knows what's going on, but more on that later. I started off with a patient I had just picked up and hadn't read about real thoroughly.

It showed.

I started with "this is a 2 year old male who presented with an acute exacerbation of asthma" and I didn't get any farther. My resident spoke up with "um, no..." and my attending jumped in with "this is unacceptable, you're wrong with the chief complaint."

See, this patient had actually come in because he had a seizure. No asthma, and he wasn't quite 2 either. I was reading the wrong notes.

I managed to piece something relating to him together, but I floundered, bad. "But," I thought to myself, "I have two more patients to redeem myself with."

This is what authorities refer to as "wishful thinking."

Patient number two is up, and I get a little farther. I manage to have the name and age right, and I even have her reason for being in the hospital down. I'm starting to relax, just glancing at the notes, when I say "an attempt was made to start a peripheral IV, but it failed, so she still has a scalp IV." This time the resident comes in with "I think you're a day behind. I placed a peripheral IV yesterday," and my attending, losing his patience with my idiocy, asks "did you even see the patient?"

Truth is, I had. It was just 6am, I'd had four hours of sleep, and I talked with her family for half an hour after my examination. I completely missed the missing scalp IV, and I just read what had been written in yesterday's progress note. This doesn't matter though, because if you can't be trusted to see, or rather note not seeing a tube 8 inches long taped to the side of your patient's head, you can't really be trusted for much.

In hindsight, this is funny.

The third patient actually went ok, I got everything right, but by that time, it was too late. I can only hope my attending and resident don't hold this one against me.

The whole experience has taught me that you shouldn't ever be too sure of yourself. You can always wind up as "one of those people."

So, on rounds this morning, I'm trying to relate the stories of each patient to the team. This is kinda funny, since everyone already knows what's going on, but more on that later. I started off with a patient I had just picked up and hadn't read about real thoroughly.

It showed.

I started with "this is a 2 year old male who presented with an acute exacerbation of asthma" and I didn't get any farther. My resident spoke up with "um, no..." and my attending jumped in with "this is unacceptable, you're wrong with the chief complaint."

See, this patient had actually come in because he had a seizure. No asthma, and he wasn't quite 2 either. I was reading the wrong notes.

I managed to piece something relating to him together, but I floundered, bad. "But," I thought to myself, "I have two more patients to redeem myself with."

This is what authorities refer to as "wishful thinking."

Patient number two is up, and I get a little farther. I manage to have the name and age right, and I even have her reason for being in the hospital down. I'm starting to relax, just glancing at the notes, when I say "an attempt was made to start a peripheral IV, but it failed, so she still has a scalp IV." This time the resident comes in with "I think you're a day behind. I placed a peripheral IV yesterday," and my attending, losing his patience with my idiocy, asks "did you even see the patient?"

Truth is, I had. It was just 6am, I'd had four hours of sleep, and I talked with her family for half an hour after my examination. I completely missed the missing scalp IV, and I just read what had been written in yesterday's progress note. This doesn't matter though, because if you can't be trusted to see, or rather note not seeing a tube 8 inches long taped to the side of your patient's head, you can't really be trusted for much.

In hindsight, this is funny.

The third patient actually went ok, I got everything right, but by that time, it was too late. I can only hope my attending and resident don't hold this one against me.

The whole experience has taught me that you shouldn't ever be too sure of yourself. You can always wind up as "one of those people."

Sunday, April 02, 2006

Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

Is hung with bloom along the bough,

And stands about the woodland ride

Wearing white for Eastertide.

Now, of my threescore years and ten,

Twenty will not come again,

And take from seventy springs a score,

It only leaves me fifty more.

And since to look at things in bloom

Fifty springs are little room,

About the woodlands I will go

To see the cherry hung with snow.

-- A. E. Housman

Saturday, April 01, 2006

Sometimes parents are the problem

One of the kids on our team is probably suffering the effects of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The only way this kid could be suffering the problems she has is if her mom is injecting the child's own feces into her IV. She keeps developing new infections, which can only come from her stool, and even swallowing the feces wouldn't cause the symptoms she has. The problem is that we can't surreptitiously put a camera in the room to watch, and having a nurse in the room at all times isn't feasible either, because we're short staffed, and it probably wouldn't make a difference because the mother has succeeded in perpetuating the child's illness while she is in the hospital, so she's pretty good at being sneaky with this. So we can't prove it, we can only treat the child, and she's not going to get better if this continues.

The other problem is that this is a very, very serious accusation, and we can't really make it unless we have proof. And we can't have proof unless someone actually sees the mother doing this. It isn't enough, legally, that when the child's grandmother stayed in her room to give the mother a break, the child got better, only to worsen when grandma left. It isn't enough that she is continually being reinfected with bugs that are susceptible to the drugs we're already giving her. It may prove the diagnosis to us, but that's not enough. At least according to my attending.

I don't like bureaucracy, I don't like feeling guilty no matter which course I choose. I just hope this mother is caught.

The other problem is that this is a very, very serious accusation, and we can't really make it unless we have proof. And we can't have proof unless someone actually sees the mother doing this. It isn't enough, legally, that when the child's grandmother stayed in her room to give the mother a break, the child got better, only to worsen when grandma left. It isn't enough that she is continually being reinfected with bugs that are susceptible to the drugs we're already giving her. It may prove the diagnosis to us, but that's not enough. At least according to my attending.

I don't like bureaucracy, I don't like feeling guilty no matter which course I choose. I just hope this mother is caught.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)